Seccion: Entrevistas (Lecturas: 5)

Fecha de publicación: Mayo de 2019

Frank J. Dello Stritto, el hombre de las dos trilogías

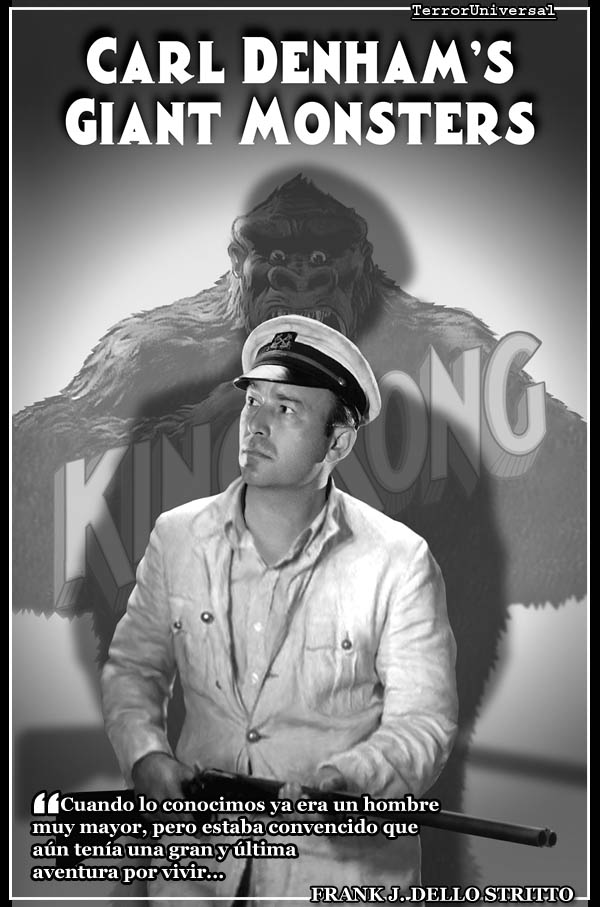

Con la novedad del lanzamiento del libro "Carl Denham's Giant Monsters" entrevistamos a su autor y viajamos de la mano de "King Kong" y de la garra de Lawrence Talbot. Darío Lavia

English version

—Contar las aventuras de Carl Denham parecería en nuestro siglo XXI un anacronismo, pero el pastiche es también una de las vertientes literarias que actualmente más atrae a los fans. ¿Cuáles fueron las influencias que te llevaron a crear Carl Denham’s Giant Monsters?

—La principal influencia, por supuesto, fueron mi recuerdos de la primera vez que vi las películas, hace tanto tiempo atrás. Recuerdo bien, a mis seis años y junto a mi familia, estar viendo King Kong en su primer pase televisivo. Esa noche mi padre estaba particularmente entusiasmado. No había visto la película desde su estreno, unos veinte años atrás.

«A pesar de que Kong sembraba el caos en New York, me llamó la atención el personaje de Carl Denham. Tal vez por ser una especie de anacronismo, o bien por estar fuera de moda. Pero un hombre que sabía lo que buscaba y que siempre trataba de conseguirlo, por las buenas o por las malas, valía la pena prestarle atención.

«De chico siempre me pregunté acerca de la vida de los personajes del cine fuera de las películas. En mi anterior libro, A Werewolf Remembers, desarrollé la vida de Lawrence Talbot así como un montón de personajes de películas de los años '30 y '40. En mi nuevo libro, trato de hacer lo mismo pero con Carl Denham y muchos aventureros del cine que, como él, persiguieron a monstruos de lo desconocido.

«Solamente unos pocos personajes no monstruosos aparecen en más de una película del cine de monstruos de aquella época y el principal de ellos es Carl Denham. Comete una afrenta en King Kong, se redime en El hijo de Kong, y luego desaparece. Sabemos que ha tenido una vida excitante antes de Kong. "¡Todos saben", dice el capitán Engelhorn, "que hay un solo Carl Denham!" No sabemos nada acerca de su vida después de El hijo de Kong, pero ¿podría un hombre tan adicto a la aventura simplemente retirarse? En mi nuevo libro están sus aventuras previas, durante y posteriores a Kong.

«En las películas, Lawrence Talbot solo se topa con un hombre lobo —Bela, el gitano que lo infesta de licantropía—. En A Werewolf Remembers se encuentra también con cada uno de los hombres lobo de los '30 y '40. En Carl Denham’s Giant Monsters, Denham siempre está en la pista de algún monstruo gigante. En ambos libros trato de tender lazos entre muchas películas diferentes que compartan una premisa en común, sea que alguien se convierta en monstruo, como Lawrence Talbot, o que persiga monstruos, como Carl Denham.

—Estas aventuras llevan a Denham por tierra, mar y aire y por unos cuantos continentes, mucho más allá de la isla de la Calavera, encontrándose en cada viaje con un diferente habitante del parnaso del cine de aventuras clásico y los opus de clase B de los estudios del callejón de la pobreza. ¿Podrías enumerar algunos de los seres más excitantes con que Denham se topa en sus múltiples incursiones en estos mundos fantásticos? En última instancia, ¿qué es lo persigue con tanto ahínco?

—El tema central del libro son las experiencias de Carl Denham con King Kong. Él narra su historia ya anciano y Kong está siempre cerca de sus pensamientos. Se siente perseguido por el inmisericorde tratamiento que diera a Kong, la culpa lo persigue por lo que Kong hizo en la aldea de la isla de la Calavera y en Manhattan. A medida que conoce otros aventureros, ve su propia vida reflejada en ellos. Por ejemplo, el profesor Challenger (de El mundo perdido), su medio hermano Max O'Hara (de El gran gorila), Carl Maia (de El monstruo de la laguna negra o La mujer y el monstruo) y Tom Friend (de El abominable hombre de las nieves). También se encuentra con los exploradores que perecerán en los escarpados de Mutia (de Tarzán y su compañera). Pero Denham también conoce personajes de la vida real, como Theodore Roosevelt (en su expedición de "El río de la duda", de 1914, en la que Roosevelt casi muere) y Frank Buck (que marchó al África junto a Abbott y Costello en busca de un gigantopiteco en África ruge o Las minas del rey Salmonete). De joven había sido reportero del famoso "juicio del mono". No sé en qué medida conozcan en Sudamérica aquel proceso judicial pero fue —y aún es— un tema muy importante en los Estados Unidos.

«En el camino también se topa con un montón de personajes extraños, vinculados con ciertas transmigraciones entre especies, como el dr. Moreau (de La isla de las almas perdidas), el dr. Renault (de El hombre sin alma) y el prof. Yamani (de Godzilla).

«Entonces, ¿qué es lo que busca Carl Denham, después de todo? Como la mayoría de los personajes que conoce, está movilizado por una búsqueda. En su caso es por el más oscuro secreto de la naturaleza lo que para él significa animales gigantes o aquello que los seres humanos denominan "monstruos", algunos de los cuales han sabido mantenerse ocultos del alcance del hombre. Tuvo su oportunidad con Kong, pero en su parecer, lo perjudicó. Cuando lo conocimos ya era un hombre muy mayor, pero estaba convencido que aún tenía una gran y última aventura por vivir, una última chance de hacerlo bien, de enmendarse.

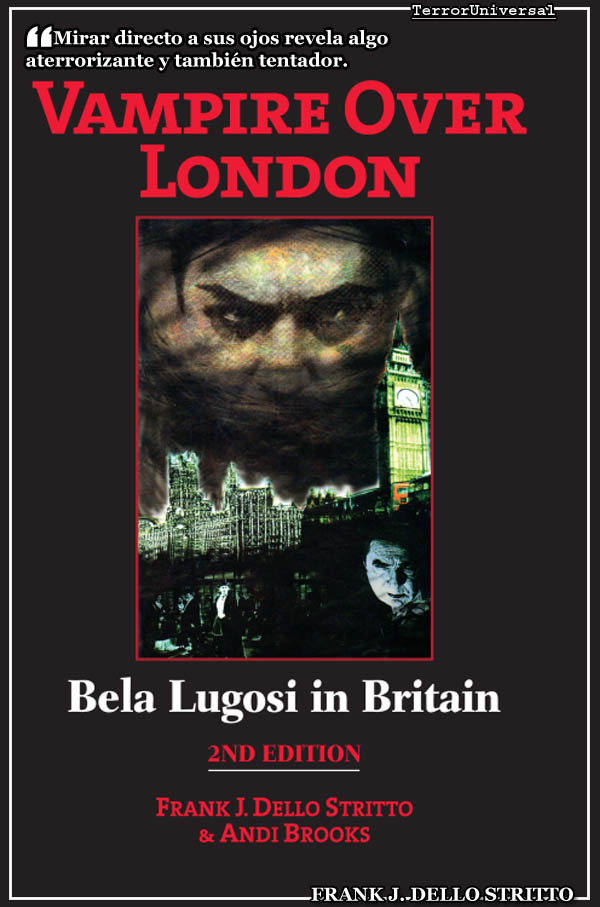

—Te conocimos a través de los sustanciosos artículos en la revista Cult Movies pero también a través de las repercusiones del libro Vampire Over London: Bela Lugosi in Britain que ha llegado a su segunda edición. Para aquel libro, Andi Brooks y tú rastrearon y entrevistaron a todos los actores, actrices y productores que aún vivían a fines del siglo pasado, recopilando una variada y muy valiosa nueva mirada acerca de Lugosi el astro y también el ser humano. ¿Por qué esa fascinación por el Gran Vampiro? ¿Cuál es tu apreciación de Lugosi en el concierto del horror clásico y frente al Inmortal Karloff?

—En primer lugar déjenme recalcar que soy un gran fan de Karloff y siempre lo seré. Pero mi fascinación —fijación, obsesión, no lo sé— con Lugosi va más allá de eso. Lo vi por primera vez caracterizado de Drácula en Abbott y Costello contra los fantasmas y quedé hipnotizado por él. Nunca antes había visto una actuación así. Creo que la razón por la que algunas estrellas realmente enganchan a determinadas personas es que proponen algo que nadie más ofrece.

«Ser un fan de Lugosi requiere paciencia porque un montón de sus películas son muy malas. Pero en el puñado de películas en las que todo gira a su alrededor, él puede ser mágico. Y audaz. Sobreactuado y sorprendentemente complejo. Una vez escribí que todos los actores que interpretan a Drácula tratan de verse extraordinarios y no lo terminan logrando. Lugosi era un hombre extraordinario tratando de verse ordinario y nunca podría convencer a nadie de que era alguien como nosotros. Sin importar cuan complejo nos parezca el Drácula de Lugosi, tenía algo sobrenatural.

«¿Qué fibra toca la personalidad cinematográfica de Lugosi en aquellos que se convierten en fans suyos? Un padre primitivo para los chicos, un amante primitivo para las chicas, una parte de nosotros mismos, un atisbo en la Oscuridad, en otro mundo que está siempre cercano a nosotros. Todo lo anterior y ¿algo más...? No lo sé... me siento muy cerca de ello.

«Abbott y Costello contra los fantasmas —si pueden separar los gags cómicos y las obligatorias escenas del monstruo— se reduce a la decisión que debe tomar Wilbur Gray (el personaje de Lou Costello). Wilbur puede quedarse con su mundanal vida, trabajando en dos empleos y tratando de labrarse una vida social sin esperar mucho. O puede adentrarse en el maravilloso y peligroso mundo de los monstruos. El conde Drácula quiere convertirlo en un ser sobrenatural, Lawrence Talbot pretende que luche contra fuerzas diabólicas. Pero Chick Young (el personaje de Bud Abbott) se la pasa trayendo a Wilbur de nuevo a su ordinaria pero inofensiva vida. Creo que ese elemento básico de la trama deAbbott y Costello contra los fantasmas es el principal motivo por el cual muchos chicos de mi generación se convirtieron en Monster Kids.

«Yo pienso que la promesa de algo maravilloso y a la vez peligroso más allá de la vida normal que conocemos puede ser una de las claves del atractivo de Lugosi. Mirar directo a sus ojos revela algo aterrorizante y también tentador.

—En A Quaint & Curious Volume of Forgotten Lore planteas que las películas de monstruos clásicos asciendan y cobren status de mito. Como las antiguas historias de dioses y semidioses, el vampiro, el monstruo reanimado, el licántropo, el hombre y la bestia, todos asumen entidad mítica, pero primero fueron escapismo pasatista en una pantalla de cine y, más tarde, de televisión. ¿Cómo pasaste de los filmes de Abbott y Costello a interesarte por los primeros estudios al respecto (como los de William K. Everson) hasta convertirte en un estudioso de la materia? ¿Qué tan lejos estás de publicar el primer ensayo estilo “La filosofía de…”?

—Como decíamos, para mí todo comenzó con Abbott y Costello contra los fantasmas. La vi en televisión, un sábado a la tarde. Me senté para ver una película de Abbott y Costello y dos horas después, era todo un Monster Kid. Hace unos años atrás, fui a un panel de fans del cine de horror. Todos teníamos más o menos la misma edad y más de la mitad de nosotros habían tenido su iniciación con Abbott y Costello contra los fantasmas. Intencionalmente o no, es la película perfecta para que un joven transite de la comedia juvenil al horror gótico.

«La gente joven de hoy en día, con la ventaja del video hogareño, nunca podrá comprender del todo la emoción y la frustración de la espera en pos de películas de las que solo se había oído hablar o leído en algun lado. A veces, películas de cuya existencia no se tenía ni siquiera idea, aparecían en televisión. Eso significaba una gran excitación. Cada nueva película era la pieza del rompecabezas de un pasado místico. Esperar a que dieran una película y tratar de conectarlas, provocó —al menos para mí— que los monstruos se convirtieran en figuras míticas. Y como en la mitología clásica, cada monstruo, cada mito tenía su propia temática sostenida de película en película. No es lugar para ahondar en detalles pero cada monstruo busca algo en particular: amor, liberación, amistad, poder. ¿Y qué es lo que persigue Drácula, además de sangre? Responder esa pregunta puede disparar una extensa discusión pero el personaje ejerce una tentación para la juventud. Ellos deben superar esa seducción para ingresar en la vida adulta.

«Para mí, las películas de monstruos eran una especie de goce privado (¿o un vicio, tal vez?) hasta que descubrí los primeros estudios serios en la materia. Sí, leí todo lo escrito por William K. Everson y tras él vinieron otros escritores que ahondaron mucho más. Me sentía muy feliz de que otros compartieran mi amor por las películas y esta gente no eran precisamente chicos como yo, sino estudiosos. Después de Everson llegó Carlos Clarens que, creo, escribió la primera historia del cine de horror. Luego un psiquiatra, Harvey Greenberg, escribió un libro sobre interpretaciones de sus filmes favoritos (que incluían King Kong, El lobo humano y El mago de Oz). Luego, cuando ya estaba en el colegio, encontré artículos periodísticos escritos por Walter Evans, que fue el primero que conocí que hizo notar las similitudes entre las viejas películas de horror y los mitos clásicos.

«Con todas estas obras y otras como base, empecé a ver a los monstruos y al cine de horror a través de una luz diferente. No me veo adoptando ese estilo de "filosofía" (y cuidado con los libros que descaradamente lo hacen, porque son ileglibles), pero me gusta creer que hay cierta filosofía en todo lo que escribo.

—En I Saw What I Saw When I Saw It, un libro cuyo título parece juego de palabras, creas un lazo nostálgico con cualquier lector que haya crecido en la década del ‘50 y ’60. Para nosotros, que crecimos en las décadas del ’70 y ’80, la televisión era fuente indispensable del cine, ya que en sus ondas habitaban los cowboys de la década del ’50, los detectives, los monstruos en colores y las criaturas gigantes, la mayoría personajes ajenos y anacrónicos a nuestro presente pre caída del muro de Berlín. ¿Qué significó la televisión en tu vida? ¿Cómo incidió tal medio en tu búsqueda por los clásicos del género, que no siempre eran emitidos ni aparecían en horarios apropiados? ¿En qué medida incidieron las prohibiciones paternas contra ver cine de terror en el auge que el género tendría en nuestra ansiedad y nuestra imaginación?

—En Abbott y Costello contra los fantasmas, el personaje de Lou Costello (y hasta el de Bud Abbott) dicen "vi lo que vi cuando lo vi" o una variante de ello. Costello se refiere a haber visto a un monstruo pero nadie le cree. Pero en mi libro yo me refería a aquello que vi en televisión (y más adelante en cine). ¿Qué tan importante fue la televisión en mi vida? La verdad es que, durante la mayor parte de mis primeros años, la televisión fue casi mi vida.

«Cuando tenía tres años de edad, mi madre quiso ver La guerra de los mundos, y me llevó al cine con ella. Me asusté hasta lo profundo de mi alma. Esto causó que en casa me sentenciaran a no ver ninguna película de terror. Mis padres podían evitar que fuera al cine pero en la televisión yo podía ver lo quisiera. Estaba sujeto a estrictos horarios para irme a la cama pero eso nunca era problema porque siempre me quedaba dormido temprano. Incluso cuando crecí y me permitían quedarme hasta tarde, no podía lograrlo. Así que tuve que esperar a que las películas de terror y de monstruos migraran a mis horarios. Para la época en que tenía diez años más o menos, ya podía ir a todas las matinés que quisiera. Vi un montón de películas ahí pero algunas muy cursis. En el cine de mi barrio solamente dieron una de las de Roger Corman (El entierro prematuro / La obsesión) y solamente una de terror de la Hammer (El fantasma de la Ópera). Así que el resto no las pude ver hasta que fui más grande.

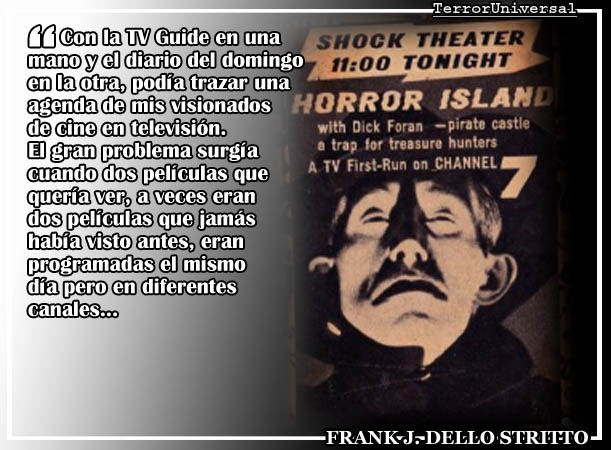

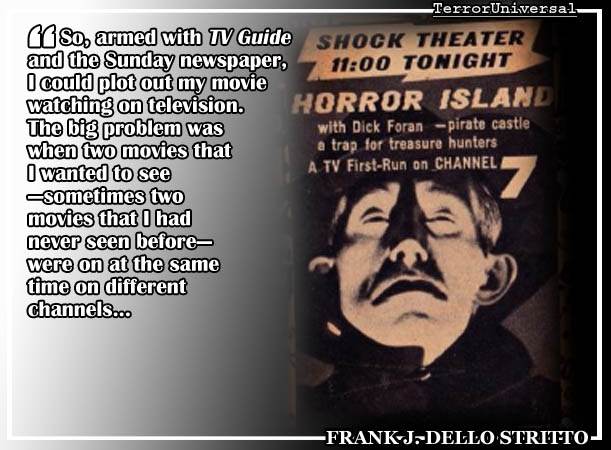

«Como te decía, me convertí en un Monster Kid luego de ver Abbott y Costello contra los fantasmas. Ahí fue cuando empecé a a escudriñar las grillas de televisión en busca de antiguas películas de terror. Vivía en New Jersey, y nuestras emisoras de televisión provenían de New York City. Teníamos siete canales (2, 4, 5, 7, 11 y 13). Esto, para la década de 1950, era un montón. No fue hasta que fui grande y trabajé en diferentes lugares alrededor de los Estados Unidos que me di cuenta de que algunos de mis compañeros de trabajo habían crecido en lugares con solo uno, dos o tres canales.

«Los diarios del domingo salían con las grillas de programación para toda la semana. Así que, los domingos, planificaba mis visionados televisivos para el resto de la semana. Pero ¿qué había en esos domingos? Salían avisos de una película que quería ver. La planificación era una cuestión sustancial ya que teníamos un solo aparato de televisión (en aquella época, un segundo televisor, así como un segundo teléfono, era lujos inimaginables... incluso en las series de televisión sobre familias que vivían en barrios suburbanos, los hogares tenían un solo aparato de televisión y un solo teléfono).

«Así que comencé a comprar la revista TV Guide. Venía los miércoles (o martes, si es que me animaba a cruzar toda la ciudad a una tienda en particular y a menudo acometía esa caminata). Traía grillas hasta el sábado. Así que, con la TV Guide en una mano y el diario del domingo en la otra, podía trazar una agenda de mis visionados de cine en televisión. El gran problema surgía cuando dos películas que quería ver, y a veces eran dos películas que jamás había visto antes, eran programadas el mismo día pero en diferentes canales. A veces trataba de ver ambas a la vez, cambiando de canal con la perilla, yendo y viniendo entre uno y otro canal. Pero eso no funcionaba muy bien, así que tenía que escoger una o la otra.

«Una vez que tenía todo planificado venía un juego de espera... o sea, la espera de que los canales emitieran las películas. Algunas películas las había visto un montón de veces. Otras, las esperaba y esperaba pero nunca se daban. La mayoría de las películas me gustaban pero la gran emoción consistía en abrir la revista o el diario y ver que tal o cual película que había esperado durante mucho iba a salir al aire.

«¿Alguna vez falté a la escuela para ver una película? No. Nunca lo hice. Los canales de televisión sabían que la mayor teleplatea de las viejas películas de monstruos eran chicos de escuela, y las daban en horarios que pudieran verlas.

«Más o menos cuando tenía 16 descubrí que los museos, los colegios y los cines de reposición en New York a veces proyectaban películas antiguas. Me hacía con los horarios y veía películas que no daban en TV.

«Ahora que lo pienso, creo que una vez sí me fui de la escuela. El día que teníamos un examen, me escapé de la clase y fui al Lincoln Center de New York para ver The Old Dark House, que se proyectaba a las 10.30 AM. Nunca había sido emitida en televisión y nunca más la volví a ver hasta que se editó en VHS.

—Hoy en día Larry Talbot ocupa el podio de Universal, si bien el tercer lugar tras Drácula y Frankenstein, su nombre es sinónimo del género. ¿Cómo llegaste a la posesión de su diario personal y qué peligros sorteaste para lograr publicarlo en A Werewolf Remembers?

—En mi libro se cuenta que cuando Lawrence Talbot marchó de Londres a Florida, tras el rastro de Drácula (al comienzo de Abbott y Costello contra los fantasmas), también hizo traer un baúl con sus pertenencias. Cuando el baúl arribó, Talbot había desaparecido para siempre (junto con Drácula, al final de Abbott y Costello contra los fantasmas). El dueño de la casa de departamentos donde se hospedaba colocó el baúl en un depósito en espera de que Talbot volviera para reclamarlo. Pero nunca lo hizo. Esa persona fue mi tío Joe (en la vida real, tuve un tío Joe que tenía una casa de departamentos en Florida) y al final el baúl cayó en mis manos. Ahí dentro estaban los diarios de Lawrence Talbot. Esos diarios fueron la base de A Werewolf Remembers.

«Su publicación no emanaba ningún peligro, así que Cult Movies Press ha publicado todos mis libros. Pero tuve que investigar mucho para respaldar la historia de Talbot. Investigación sobre los lugares en que vivió y visitó, sobre licantropía y vampirismo, y sobre los extraños asesinatos que describe. Cuando al principio leí los diarios, me dio la impresión de que Talbot sufría alucinaciones. Pero todo lo que escribió encajaba con los hechos que investigué. Al comenzar la lectura de los diarios, yo era un escéptico. Pero para el momento de concluir, me había convertido en un creyente. Lawrence Talbot fue un hombre lobo que luchó contra un vampiro.

—Cada una de tus publicaciones toca una nota diferente en el arpegio del cine de horror clásico. Si bien el libro de Carl Denham está bien caliente salido de la imprenta, ¿qué ideas o proyectos tienes en mente para el futuro –siempre y cuando se puedan revelar—?

—Estoy trabajando en un nuevo libro. Aún no puedo revelar los detalles, pero les daré una pista. Lawrence Talbot apareció como personaje en cinco películas. A Werewolf Remembers une todas esas películas y unas cuantas más. Carl Denham apareció en dos películas y Carl Denham’s Giant Monsters las une junto a los monstruos de un montón de otras películas. Para A Werewolf Remembers, me basé en los diarios de Talbot. Carl Denham’s Giant Monsters estaba basada en las charlas que mi esposa y yo tuvimos con Denham cuando vivimos en Indonesia (en la vida real, durante un tiempo estuvimos en Indonesia). Denham estaba ya muy viejo, recluído en una pequeña isla. Pero a lo largo del año o dos que nos frecuentamos, nos contó toda su historia.

«Así que, hay otros personajes que aparecen en múltiples películas y cuyas historias deben ser contadas. En eso es en lo que estoy trabajando ahora.

«Mis primeros tres libros, Vampire Over London – Bela Lugosi in Britain, A Quaint & Curious Volume of Forgotten Lore – The Mythology & History of Classic Horror Films y I Saw What I Saw When I Saw It – Growing Up in the 1950s & 1960s with Television Reruns & Old Movies, forman una trilogía: una historia, un análisis y unas memorias. También están disponibles en forma de boxset (Cult Movies Press Horror Trilogy).

«Mis siguientes tres libros, A Werewolf Remembers, Carl Denham’s Giant Monsters y el libro en el que estoy ahora trabajando, formarán una segunda trilogía (Cult Movies Press Monster Trilogy) que espero que esté disponible para 2021. Y ese puede que sea el último de mis libros. No tengo más planes después de eso.

—Realmente esta charla fue un lujo y un honor, Frank, porque además de aprender repasamos también nuestro propio pasado. Muchas gracias por tu tiempo y dedicación. Y a todos los lectores recomendamos calurosamente dirigir sus cibertimones a Cult Movie Press para más información sobre contenidos y pedidos de estas obras.

English version

—The adventures of Carl Denham would seem an anachronism in our XXI century, but pastiche is also one of the literary slope that currently attracts the most fans. What were the influences that led you to create Carl Denham's Giant Monsters?

—Well, of course, the main influences are my memories of first seeing the movies so long ago. I remember well, when I was six years old, watching King Kong’s television premiere with my family. My father was particularly excited that night. He had not seen the movie since it first came out, over 20 years before.

«Even with Kong rampaging through New York, I still noticed Carl Denham. Maybe such a character has become an anachronism, or maybe he is just out of the current fashion. But a man who knows what he wants, and intends to get it is always, for good or bad, someone worth watching.

«As a boy, I always wondered about the lives of movie characters outside their movies. In my earlier book, A Werewolf Remembers, I developed the lives of Lawrence Talbot and a lot of movie characters in 1930s and 1940s movies. In my new book, I try to do the same for Carl Denham, and many movie adventurers like him who seek monsters in the unknown.

«Only a few non-monstrous characters appear in multiple 1930s and 1940s monster movies, and chief among them is Carl Denham. He sins in King Kong, is redeemed in Son of Kong, and then disappears. We know that he had an exciting life before Kong. “Everybody knows,” says Captain Engelhorn, “there’s only one Carl Denham!” We know nothing about his life after Son of Kong, but could a man so addicted to daring and adventure have simply retired? In my new book, he has a full life before, during and after Kong.

«Now, in the movies, Lawrence Talbot meets only one werewolf—Bela the Gypsy who infects him with lycanthropy. In A Werewolf Remembers, he meets almost everyone werewolf from the 1930s and 1940s. In Carl Denham’s Giant Monsters, Denham is always on the trail of giant monsters. In both books, I try to tie together quite distinct movies that share a common premise, whether that be becoming a monster, like Lawrence Talbot, or searching for monsters, like Carl Denham.

—These adventures take Denham by land, sea and air and through a few continents, fair beyond Skull Island, meeting on each trip a different inhabitant of the realm of the classic adventure movies and the B opus of the poverty row. Could you list some of the most exciting beings Denham encounters in his multiple forays into these fantastic worlds? Ultimately, what is he chasing so hard?

—The core of the book is Carl Denham’s experiences with King Kong. As an old man, as he narrates his story, Kong is never far from his thoughts. He is haunted by his callous treatment of Kong, and by his guilt over what Kong did to the village on Skull Island, and in Manhattan. He sees his own life story reflected in the other adventurers that he meets. They include Professor Challenger (from The Lost World), his half-brother Max O’Hara (from Mighty Joe Young), Carl Maia (from Creature from the Black Lagoon), and Tom Friend (from Abominable Snowman of the Himalayas). He encounters explorers who will perish on the Mutia Escarpment (from Tarzan & His Mate). Denham also meets some real-life characters, like Theodore Roosevelt (on his 1914 “River of Doubt” expedition, on which Roosevelt almost died) and Frank Buck (who with Abbott & Costello, searches for a giant ape in Africa Screams). As a young man gets a job as a reporter for the Scopes Monkey Trial. I don’t know how well the trial is unknown in South America, but it was—and is—a very big deal in the United States.

«Along the way, he also meets a lot of strange characters who are involved in ape-to-man species transmigration, like Dr. Moreau (from Island of Lost Souls), Dr. Renault (from Dr. Renault’s Secret) and Prof. Yamani (from Godzilla).

«So, what is Carl Denham looking for? Like most of the characters that he meets, he is driven by a quest. His quest is to find the deepest of nature’s secrets, and for him that means giant animals—what we humans called “monsters”—which somehow have stay hidden from Man. He had his chance with Kong, but in his mind, he bungled it. When we meet him in the book, he is a very old man, but believes that he has one last adventure in him, one last chance to get it right.

—We met you through the meaty and solid articles in the Cult Movies magazine but also through the aftermath of the book Vampire Over London: Bela Lugosi in Britain that has reached its second edition. For that book, Andi Brooks and you tracked and interviewed all the actors, actresses and producers who still lived at the end of the last century, compiling a assorted and very valuable new look about Lugosi the star and also the human being. Why this fascination with the Great Vampire? What is your appreciation of Lugosi in the classic horror concerto and in front of the Immortal Karloff?

—First, let me stress that I am a big fan of Karloff’s, and always have been. But my fascination—fixation, obsession, I don’t know—with Lugosi went beyond that. I first saw him as Dracula in Abbott & Costello Meet Frankenstein, and was mesmerized by him. I had never seen anything like his performance before. I think that is why some movie stars really hook some people—they offer something that no one can.

«Being a Lugosi fan takes patient, because a lot of the movies that he made are very bad. But in the handful of movies where everything works for him, he could be magical. And audacious. Over-the-top, and surprisingly complex. I wrote once that most actors who play Dracula are trying to look extraordinary, and don’t quite pull it off. Lugosi was played an extraordinary man, trying to look ordinary, and not quite convincing anyone that he is one of us. No matter how hard Lugosi’s Dracula to pass among us, there was something otherworldly about him.

«So, what does Lugosi’s screen persona tap in those who become devoted to him? The primal father for boys, a primal lover for girls, a part of ourselves, a glimpse into a dark netherworld that is always near us. All of the above, and something else? I don’t know—I am too close to it.

«Abbott & Costello Meet Frankenstein—if you strip away the comic antics and the obligatory monster scenes—boils down to the choice offered Wilbur Gray (the Lou Costello character). Wilbur can stay in his mundane life, working two jobs, trying to carve out a social life, not much to look forward to. Or he can enter the wonderful, dangerous world of monsters. Count Dracula wants him make him supernatural, Lawrence Talbot wants him to battle supernatural evil. But Chick Young (the Bud Abbott character) keeps pulling Wilbur back to the ordinary, unexciting but safe life. I think that basic plot element in Abbott & Costello Meet Frankenstein is the main reason why so many of my generation became Monster Kids.

«And I think that promise of something wonderous and dangerous beyond the normal life we know may be a key to Lugosi’s appeal. Looking into his eyes reveals something terrifying and seductive.

—In A Quaint & Curious Volume of Forgotten Lore you suggest that classic movie monsters rise to get myth status. Like the ancient stories of gods and demigods, the vampire, the reanimated creature, the werewolf, the doctor and the beast, all assume a mythical entity, but first they were escapism, a pastime on a cinema screen or, later, television. How did you go from Abbott and Costello to get interested in the first studies on the subject (like those of William K. Everson) and to become a scholar of the subject-matter? How far are you from publishing the first essay “The philosophy of..." style?

— As I said, it started for me with Abbott & Costello Meet Frankenstein. I saw it on television on a Saturday afternoon. I sat down to watch an Abbott & Costello movie, and two hours later, I was a Monster Kid. I was on a panel of horror movie fans a few years ago. We were all about the same age and more than half of us got our start with Abbott & Costello Meet Frankenstein. Intentionally or not, it is the perfect movie to transit a young viewer from juvenile comedy to gothic horror.

«Young people today, with the advantage of home video, cannot really understand the thrill and frustration of waiting to see movies that we had only heard or read about. Sometimes, movies we never heard of popped up on television. That was excitement. Each new movie was a piece in the puzzle of a mystical past. Waiting for the movies to come, trying to connect them, made the monsters—at least for me—mythical figures. And as in classical mythology, each monster, each myth had its own theme that carried from movie to movie. I won’t go into the details here, but each monster searches for something: love, release, friendship, power. And what is Dracula after, besides blood? That can be a long discussion, but he is a temptation to the young to follow him. They must overcome that seduction to enter adult life.

«For me, monster movies were pretty much a private joy (vice?) until I discovered the first serious writings on them. Yes, I read all the writings of William K. Everson, and in his wake came writers who went much deeper. I was so happy that others shared my love of the movies, and that they were not just kids like me, but scholars. After Everson came Carlos Clarens, who, I think, wrote the first book-length history of horror films. Then a psychiatrist, Harvey Greenberg, wrote a book on interpretations of his favorite films (which included King Kong, The Wolf Man, and The Wizard of Oz). Then, when I got to college, I found journal articles written about the same time by Walter Evans, who was the first that I knew of who dwelled on the similarities between old horror films and classical myths.

«With those works and others as a basis, I was launched into seeing monster and horror films in a different light. I don’t see myself adopting a “philosophy of” style (and beware books that too blatantly do—they are unreadable), but I like to think that some philosophy in everything that I write.

—In I Saw What I Saw When I Saw It, a book whose title looks like a wordplay, you create a nostalgic bond with any reader who grew up in the 50s and 60s. For us, who grew up in the 70s and 80s, televisión was essential, necessary source of cinema since in their waves lived cowboys of the 50s, detectives, the monsters in color and the giant creatures, most characters outside and anachronistic to our time pre-fall fo the Berlin Wall. What did television mean in your life? How did television affect your search for the genre classics, which were not always showed or appeared at proper hour? To what extent did the paternal prohibitions against watching horror films affect the rise that the genre would have in our anxiety and our imagination?

—Seven times in Abbott & Costello Meet Frankenstein, the Lou Costello character (and once, the Bud Abbott character) says “I Saw What I Saw When I Saw It” or a variant of it. Costello is talking about seeing monsters, but no one believes him. For my book. I was talking about what I saw on television (and later at the movies). So, was television important in my life? Well, for most of my first years, television almost was my life.

«When I was three-years-old, my mother wanted to see War of the Worlds, and took me to the theatre with her. Itscared the hell out of me. That led to a dictum in our home that I not see any scary movies. My parents could stop me from going to a theatre, but I could always watch whatever I wanted on television. They did have firm bedtimes for me, but that was never a factor—I always fell asleep early. Even when I was older, and was allowed to stay up later, I just couldn’t make it. So, I had to wait for monster and horror movies to migrate to my hours. By the time I was 10 or so, I could go to any Saturday matinee that I wanted to. I saw a lot of horrors there, but pretty cheesy ones. Only one of the Roger Corman Poe movies (Premature Burial) and only one of the Hammer horrors (Phantom of the Opera) ever played at my neighborhood theatre. So, I didn’t see them until I was much older.

«As I said, I became a Monster Kid after seeing Abbott & Costello Meet Frankenstein. That’s when I started scouring the television listings for old horror movies. I lived in New Jersey, and our television broadcasts came from New York City. We got seven stations (channels 2, 4, 5, 7, 11 and 13). That was a lot for the 1950s. It wasn’t until I was a grown man, and worked in different places around the USA that I realized that some of my co-workers had grown with only one or two or three stations.

The Sunday newspapers gave television listings for the week. So, on Sunday, I plot my television viewing through the next week. But what about Sunday? I only had hours notice of a movie that I wanted to see. Planning for important because we only had one television (in the 1950s, a second television, like a second telephone, was an unimagined luxury—even on the television series with families living in big suburban homes, had only one television and phone in the house).

«So, I started buying TV Guide magazine. It came out on Wednesdays (Tuesdays, if I walked across town to a special store, and I often made that walk). It gave listings for the next Saturday through Friday. So, armed with TV Guide and the Sunday newspaper, I could plot out my movie watching on television. The big problem was when two movies that I wanted to see—sometimes two movies that I had never seen before—were on at the same time on different channels. I tried switching back and forth between them. That didn’t work so well, so I had to choose one or the other.

«After all that planning was a waiting game—waiting for the television stations to broadcast the movies. Some movies I saw a lot of times. Some movies I waited and waited for, and they never came. I liked most of the movies, but the big thrill was opening the magazine or newspaper and seeing that a movie that I had been waiting for was going to air.

«Did I ever skip school to see a movie? No. I never really had to. The television stations knew that the biggest audience for old monster movies were school kids, and aired them when we could see them.

«At about age 16, I discovered that museums, colleges and revival theatres in New York sometimes showed rare old films. I would collect their schedules and see films that weren't on TV.

«Well, I guess I did skip school once. In college, on the day that we were due for a quiz, I cut class to go to Lincoln Center in New York to see The Old Dark House, which played at 10:30 am. It had never been on television, and I would not see it again until the movie came out on VHS.

—Today Larry Talbot fill the podium of Universal, although the third place after Dracula and Frankenstein, his name is synonymous with the genre. How did you get to own his personal diary and what dangers did you manage to get published in A Werewolf Remembers?

—In my book, we learn that when Lawrence Talbot left London for Florida, in pursuit of Dracula (in the beginning of Abbott & Costello Meet Frankenstein), he also shipped a steamer trunk of his belongings. By the time the trunk arrived, Talbot had disappeared forever (along with Dracula, at the end of Abbott & Costello Meet Frankenstein). The owner of the apartment house where Talbot had rented rooms put the trunk in storage, and waited for Talbot to claim it. He never did. That owner was my Uncle Joe (in real life, I had an Uncle Joe who owned an apartment house in Florida), and eventually the trunk fell into my hands. In it were Lawrence Talbot’s journals. Those journals are the basis for A Werewolf Remembers.

«No dangers in getting it published. Cult Movies Press publishes all my books. But I had to do a lot of research to back up Talbot’s story. Research into the places he lived and visited, into lycanthropy and vampirism, into the strange murders that he describes. When I first read the journals, I was sure that Talbot was delusional. But everything that he claims squares with any facts that I could find. When I began reading the journals, I was skeptical. By the time I finished, I had become a believer. Lawrence Talbot was a werewolf, who battled a vampire.

—Each of your publications plays a different note in the arpeggio of classic horror cinema. While Carl Denham book is very hot, recently out of print… What ideas or projects do you have in mind for the future -as long as they can be revealed?

—I am working on a new book. I am not ready to reveal the details, but I will give you a hint. Lawrence Talbot appears as a character in five movies. A Werewolf Remembers ties those movies, and a lot of other movie tales together. Carl Denham appears in two movies, and Carl Denham’s Giant Monsters ties them and a lot of other giant beast movies together. For A Werewolf Remembers, I had Talbot’s journals. Carl Denham’s Giant Monsters is based on my wife’s and my meetings with Denham when we lived in Indonesia (in real life, we once lived in Indonesia). Denham was then a very old man, living in seclusion on a small island. But he told us his story over the year or two that we knew him.

«So, there’s other characters that appear in multiple movies, and whose tales need to be told. That’s what I am working on now.

«My first three books (Vampire Over London – Bela Lugosi in Britain, A Quaint & Curious Volume of Forgotten Lore – The Mythology & History of Classic Horror Films, and I Saw What I Saw When I Saw It – Growing Up in the 1950s & 1960s with Television Reruns & Old Movies) form a trilogy: a history, an analysis and a memoir. They are available as a boxed set (Cult Movies Press Horror Trilogy).

«My next three books,A Werewolf Remembers, Carl Denham’s Giant Monsters and the book that I am working on now will be a second trilogy (Cult Movies Press Monster Trilogy). I hope that it will be available in 2021. And that may be the last of my book writing. I have no plans beyond that.

Really this talk was a joy and an honor, Frank, because in addition to learning we also review our own past. Thank you very much for your time and dedication. And to all readers, we warmly recommend directing his browsers to Cult Movie Press for more information about contents and orders for these books.

| atrás

| recomendar esta página

| enviar comentarios

| arriba

| |